Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Michelle on To the Lighthouse

My first impression of the section ‘Time Passes’ is that although Woolf is famous for her constantly shift of vantage points style of writing, but one may never expect that there would be a whole section written from the point of view of the passage of time.

My second impression would be that Woolf is trying to present to her reader a fiction with the quality of a film, where all the senses are stimulated except olfaction. More than one thing happens at once. Her way of capturing the muse seems to determine the way she writes. She said in an article that, with

‘a sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it; and in writing, one has to recapture this, and set this working and then, as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it.’

This way of writing is just like a director making a film, he or she will draw a storyboard first and then write down all the details he/she wanted in the script, ‘Time Passes’ is like a two hour movie consists of a series of still images and with brilliant montages and clever cuts, as well as a none-linear narrative.

It was known that Woolf struggled the most in constructing the section ‘Time Passes’. She had a clear structure in mind before she wrote To the Lighthouse. In her notebook (‘Notes for Writing’), the notes for To the Lighthouse begin: ‘All character-not a view of the world. Two blocks joined by a corridor.’ The shape on the notebook looks like an H. We also notice that her obsession with shape throughout the book actually started with the structure of the book.

We can also say that like a painter transforms vision into design, that Woolf transforms her impressions into words and stories. It is discussed by many critics that Woolf started To the Lighthouse with series of stories. Then the role of the middle section ‘Time Passes’ is an interlude which transforms the stories into novel by connecting the past and the future.

Time Passes is also a break from the narrative down the middle of the book, like lily’s line down the middle of her painting, is a break from traditional way of writing as well as Woolf’s own childhood.

The core of the first half of Time Passes is death. Death of the house, of people, and of the objects.

‘The house was left; the house was deserted.’ ‘The sauce pan had rusted and the mat decayed’ ‘The place was gone to rack and ruin.’ P.150.

Almost indicentally we learn of Mrs. Ramsay’s death, and the death of Prue and Andrew. ‘Mrs. Ramsay having died rather suddenly the night before…’p.140.

This section marks a new beginning, a reborn; raised from the dead, a new form of language and shape of fiction is invented. After the first half of the section where all is dead and quiet, Mrs. McNab came into the house and brought a breath of fresh air. She is an intruder of the silence. When she opens the Windows which framed the past, it signifies a beginning of another era. Since then, the objects in the house are given lives. However, the ghost of Mrs. Ramsay keeps coming back and speaks to Mrs. McNab, being an old woman, at one point she lacks the strength to fight with the old, mouldy past.

‘The books and things were mouldy, for, what with the war and help being hard to get, the house had not been cleaned as she could have wished. It was beyond one person’s strength to get it straight now.’ p.147.

Then Woolf continued to say that

‘People should come themselves; they should have sent somebody down to see.’ P.148. Later on when more people came to help, the house is clean again. Is Woolf saying that to clean the old way of writing and embrace the new need not only one person’s contribution but people’s collaborative work?

Woolf’s style is all about rhythm. Rhythms of perceptions, of emotions and of atmosphere. Woolf uses asyndeton on purpose in order to accelerate the pace of the movement of time, so that the reader feels the time flies in this section. For example, ‘the torn letters in the wastepaper basket, the flowers, the books, all of which were now open to them and asking…’ p.138.

Woolf is a master in the use of anaphora as well. Her use of anaphora appears all over the section:

‘Let the wind blow; let the poppy seed itself and the carnation mate with the cabbage. Let the swallow build in the drawing-room…’p.150 and in p.139

‘at length, desisting, all sighed together; all ceased together, gathered together, all sighed together; all together gave off an…’1 which also has the quality of polysyndeton. Anaphora serves to tie multiple sentences or paragraphs together, which causes the continuity in the flow of images and thoughts in the narrative. This also supports the technique stream of consciousness as it is based on the flow of thought in the mind without permitting any interruption.

One interesting quote from Allen McLaurin I thought is enlightening is this: ‘Virginia Woolf uses parentheses as something more than a mere device in the novel, for the whole form can be seen as a parenthesis. The first and last sections, being parallel, form brackets around the central section, seeing the novel as a "whole shape,"2 McLaurin connects this section with Lily Briscoe's problem of painterly form: "the thin central section is like a vertical line, as well as being an empty space bracketed by the first and last sections." Her intent here is thus to "make the novel approximate as nearly as possible to the visual effect of a painting."2

Discussion point: Minta's song, "Damn your eyes," suggests the precariously enabled limit of any one person's judgment: the other's gaze. How can we know or represent the "truth" of something not only if we are subjectively positioned in space and time, but if the social frame we want to criticize or evaluate is the one that determines the limits of our vision?

Footnotes 1.V. Woolf. To the Lighthouse, Penguin Group, Australia, 2010 2. J. M. Haule, V.Woolf, C.Mauron "Le Temps Passe" and the Original Typescript: An Early Version of the "Time Passes" Section of To the Lighthouse, Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Autumn, 1983), pp. 267-311, Hofstra University Viewed on,29/03/2011 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/441468

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

Stein reading her own work: online access

Enjoy!

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

Gertrude Stein- Reading

Gertrude Stein

“In Gertrude Stein's writing every word lives... it is like a kind of sensuous music... listening to Gertrude Steins' words and forgetting to try to understand what they mean, one submits to their gradual charm.” (Mabel Dodge Luhan in ‘Speculations’, 1913)

As romanticised as the above quote is, Gertrude Stein’s work is not one easily conquered. Instead, you start to find yourself having to “work hard” for reader-satisfaction. “Working hard” as a reader in Stein’s text is to struggle and to challenge the conventions of writing and the act of reading. It is the experience of language and the power of words that have poignancy in Stein’s portraits, instead of being propelled by the subject matter we are compelled to acknowledge the strength in words to depict the person. Critic, Ulla Haselstein, aptly describes Steins work as “abstract word collages”, the language is simple and child-like reminiscent of a tongue twister or nursery rhyme.

Furthermore, a sense of bewilderment in vocabulary is experienced, language is intentionally limited, words that one encounters daily are arranged in such a way as to feel like a foreigner in your own language. Our sense of authority over a text through the act of reading has been undermined. Instead reading has been reduced to something elementary, child-like, our expectations are subverted and even insulted because simple sentences become confusing. This word play is evident in Miss Furr and Miss Skeene,

“she was always learning little things to use in being gay, she was telling about other ways of being gay, she was telling about learning other ways in being gay, she was learning other ways in being gay, she would be using other ways in being gay, she would always be gay in the same way...” (p8)

In Miss Furr and Miss Skeene we find a sense of theatricality to this portrait that reduces the reader to a state of hilarity. This work demonstrates the importance of sound and it is the repetition of words in different arrangements such as ‘gay’ and ‘regular’, that highlights the importance of not only reading but listening to the sentence to enjoy its full effect.

Initially her works appear to be less about enjoyment and that achievement is found in understanding the work (if ever) rather than finishing the work. Movement through the text seems cyclical and repetitive leaving the reader puzzled. Although Steins portraits give the illusion of repetitiveness, each sentence remains slightly different, forcing the reader to reflect with the text, which is evident in the portrait Pablo Picasso,

“One whom some were following were completely charming. One whom some were certainly following was one who was charming. One who some were following was one who was completely charming. One whom some were following was one who was certainly charming”. (p3)

Again we see in this extract that Stein plays on the arrangement of words and the way they impact upon each sentence. Shifting the key words “certainly” and “charming” throughout the passage encourages us to listen to and consider each sentence as a portrait in itself.

Additionally, in Julian Murphet’s lecture on Stein, he highlighted the way Stein’s portraits had a sense of immediacy that was “without remembering”. Therefore, most of her portraits attempted to avoid description, rather Haselstein believes Stein’s preoccupation was with the psychological state of those she was writing about, particularly in the portraits of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. Exploration into the psyche can be evident in the depiction of Henri Matisse;

“...he had been trying to be certain that he was wrong in doing what he was doing and when he could not come to be certain that he had been wrong in doing what he had been doing ... he was really certain he was a great one and he certainly was a great one”. (p2)

In conclusion, Stein’s work does have a “gradual charm” that can lead the reader to feel a sense of enjoyment in the challenge of reading and listening. Stein’s ability to subvert the conventions of writing and language successfully provokes the reader to question the way we experience and appreciate language.

Discussion point: What value does Stein’s work have today?

References:

Haselstein, Ulla (2003), Gertrude Stein's Portraits of Matisse and Picasso in New Literary History, Baltimore, Vol. 34, Iss. 4; pg. 723, 21 pgs

Gertrude Stein and Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea

My very first impression upon reading Gertrude Stein’s prose was that maybe, somehow, my reader was printed incorrectly. My second impression was a simple thought; maybe there is more here than what first meets the eye, perhaps Stein merely wanted to lead the reader into a false sense of poetic and rhythmic gibberish and hoped that someone out there got more from her words than what was merely on the page.

Stream of consciousness: stream of consciousness is simply writing what comes to mind and continuing to do so until either time runs out or you’ve exhausted your mind’s reserves for such weird and fascinating thoughts and while these thoughts are actually being paid attention to they thunder loudly in your head and low and behold it’s raining outside which can bring thunder which scares me a little but lightning is nice…

THIS is what Stein does, at least what I believe she wanted to put forth to her readers; this sense of being inside her head or the heads of the her characters in such a modernist way that it allows the reader to flow through and with these thoughts and images and feelings like it really is a stream. This can be seen clearly in many, if not all of her works, in particular the poem ‘Susie Asado.’

Lines and words within the first half of the poem conjure in my mind the image of the narrator sitting down to a formal tea. The line: “When the ancient light grey is clean it is yellow” gives me the impression that the narrator is describing tea leaves before and after infusing them in hot water. The line: “This is a please this is a please there are the saids to jelly” implies to me the small talk and conversations taking place as they are drinking tea. What link all of this together in my own mind are the lines:

A pot. A pot is the beginning of a rare bit of trees. Trees tremble, the old vats are in bobbles, bobbles which shade and shove and render clean, render clean must. (pp. 5 (13).

I got the image of the tea pot and the idea that the narrator is connecting “trees” with the tea leaves as leaves grow on trees and tea leaves need to “tremble” and “shove” and be strained clean to have drinkable tea. All of these images can be linked with the idea of Stein writing, or indeed creating, a stream of consciousness where everything is linked in some obscure way.

These connections can also be seen in the following lines:

Drink pups drink pups lease a sash hold, see it shine and a bobolink has pins. It shows a nail.

What is a nail. A nail is unison. (pp. 5 (13).

The reader may not get anything from such a seemingly nonsense procession of words but if we were to follow the idea that maybe this was simply a stream of Stein’s consciousness we can start to see patterns and connections between these sentences. Firstly, “lease a sash hold” brings to the reader’s mind the idea that a sash is used to hold something in place, to connect pieces together that would otherwise be awry.

As the ‘stream’ progresses and the reader follows on to the idea of a “bobolink” which is a black bird and the collective noun for these birds is a chain, we can start to see possible connections. The poem then states that “a bobolink has pins” and “It shows a nail”; again the reader can see the progression in ideas from a sash, to a ‘chain’, to pins and a nail, all devices that connect or bring things together, culminating in the line “A nail is unison”, possibly the simplest way Stein could convey links between two things and the actual embodiment of the connection itself: the nail.

From this, are we to infer that the “sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea” is what brings to Stein’s consciousness the image or indeed memory of Susie Asado? Indeed, the lines: “Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea/ Susie Asado” are repeated quite often throughout the poem and perhaps drinking tea conjures Asado for Stein as the use of repetition puts forth an emphasis to the reader and shows that this is important.

Upon reflection, it can be deduced that my conclusions here indicate the possibility that there is indeed more the Stein's prose than the seeming gibberish that meets the eye of the reader and alludes to the fact that she may have used writing through a stream of consciousness to get these deeper meanings across.

There is, however, always that underlying worry that maybe I have been misled and this was all part of Stein's plan; to make the reader search for meaning amongst this random collection of words, to be lead and perhaps to lead ourselves, down our own stream of consciousness.

Monday, March 14, 2011

Gertrude Stein and Aesthetics

I cannot decide if Gertrude Stein's unconventional writing is real, aesthetically pleasing and novel art. Stein’s writing is like nothing I have encountered before. It is impressive as she essentially is reinventing language and playing with grammatical rules. However, I feel this is even too far for the Modernist era. The reader is imprisoned by an unclear collage of words and trapped in the nothingness behind her writing; Stein is isolating her readers. Modernists often compromise the aesthetic component of their art in order to shock their audience.

Nevertheless, whether I find her writing to be simply annoying or real innovative prose (if we can even call it that?), Stein's experimental writing follows Ezra Pound’s motto “make it new” wholly. Stein embodies the Modernist era as her writing is composed of distorted word meanings, illogical repetition, puns and a musical flow that creates utter chaos in her work. This results in a repetitive child-like type of prose without a story and rather utilizes general and simple words.

Stein created her own language, as the content of her “portraits” is full of repetitive rambling and meshed words with non-literal meanings. For this reason, the aesthetic value of Stein's work must be debated. While some find her writing to be pure nonsense and a random assortment of words, others find the newness of language as beautiful and melodic creativity. I do not know where I stand on this. I can appreciate the mere novelty of her craft but often leave each piece not knowing what I have read. It is frustrating; is she mocking her reader? What am I supposed to get out of these pieces?

Since the text is non-referential, meaning the words only refer to themselves, not their semantic meanings, we may never know what Stein’s intent was behind her writing. She essentially plays with her readers as she disposes of all signifiers in language, leaving the words to be sounds that can mean virtually anything. The following excerpt is from the double portrait “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene:”

They were in a way both gay there where there were many cultivating something. They were both regular in being gay there. Helen Furr was gay there, she was gayer and gayer there and really she was just gay there, she was gayer and gayer there, that is to say she found ways of being gay there that she was using in being gay there.

When reading this aloud, these sentences sound like a rhyming, bouncy, and childish nursery rhyme. The repetition and basic words contribute to the rhythmic flow. This is an example of a piece that I had less difficulty with. This portrait, from what I have deduced, tells the story of two happily gay women in love. It is impressive that one can come to a conclusion of what this portrait is expressing of the women’s personalities without quantitative information. However, I only get a general idea of the piece; I could not explain details or even give translations of the individual sentences.

Stein’s writing can be utter crazinesss at times; this excerpt is from her novel “Tender Buttons,” and is under the heading: SHOES.

"To be a wall with a damper a stream of pounding way and nearly enough choice makes a steady midnight. It is pus.

A shallow hole rose on red, a shallow hole in and in this makes ale less. It shows shine."

While the heading is "SHOES," the actual text does not seem to have much to do with shoes. I find when I try to make sense of this excerpt and relate it to the heading, I leave more confused. The purpose of this piece is not to make literal sense and does not tell a story. Stein’s portraits can indeed characterize a person using the same style, but her novel “Tender Buttons” is full of lists and descriptions that I cannot decode. The above text does indeed hold an aesthetic aspect; this excerpt also sounds like a nursery rhyme as it oozes musicality and has a sort of rhythmic flow.

Stein's writing is often compared to cubism, as it is also difficult to understand the analogies of shapes, words, lines, and so on in Cubist art. In today’s word, Cubism as an aesthetic form of art is not debated. However, Gertrude Stein’s prose is. Moreover, if this comparison is made, Stein’s art must have the potential to be aesthetically pleasing. We do not need to understand what the art is to consider it aesthetically pleasing art. It is unlikely that all understand the intertwining shapes, images, and colors in Pablo Picasso’s work. Nonetheless, it is famed as beautiful art. Stein must be looked at similarly; Stein’s art is pretty to look at, too, even if one is confused in what it is. Its mere presence of innovation demands aesthetic value.

Stein is performing with words as they muddy and mesh together to make sounds. By the end of reading one of these pieces, there most likely will not be clarity or closure. The only conclusion I can come to is that this is not a typical piece of literature where themes, conventional use of grammar, advanced vocabulary, and even specific nouns exist. Stein is protesting the conventional; she is rewiring what typical communication is by using words differently than ever before.

As I am finishing this blog entry, I find that I have convinced myself that Gertrude Stein’s writing is indeed aesthetically pleasing art. It is excitingly strange and original. It simply sounds fun when read aloud. Her text is deceivingly simple; or is it? The message behind her writing could be incredibly intricate but I do not know and I am OK with that. Experts and professors may theorize what a certain portrait or list really means but it is honestly impossible to ever know Stein's motives behind this eccentric and erratic writing. When words are stripped of their meanings, then the text can mean anything. This type of writing should be taken for what it is: a hodgepodge of words that sound nice together.

My conclusion is this: the aesthetic value is found in one getting lost in the floating repetitive sounds and awkward word pairings, without picking at any apparent themes. Finding thorough and cohesive meaning in writing was obviously too much of a cliché for Gertrude Stein.

Saturday, March 5, 2011

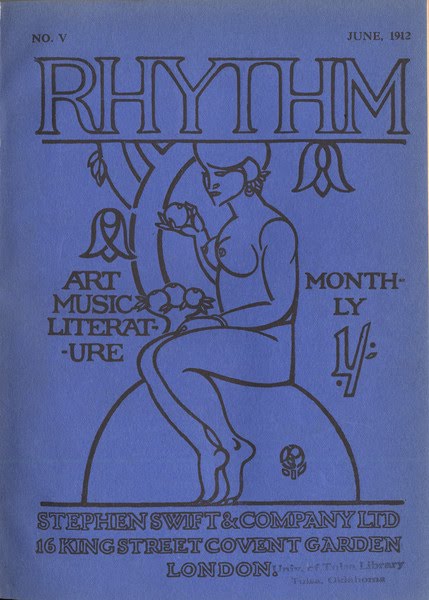

I named this tutorial's blog after a modernist magazine, Rhythm, founded by the English critic and editor John Middleton Murry in 1911. Murry was only 21 or 22 when he started the magazine. The name alludes to the philosophy of Henri Bergson, which had a huge influence on artists and intellectuals at the start of the twentieth century. Murry himself said ‘Modernism means Bergsonism in philosophy’.

The magazine published some woodcuts, like this cover image by the Scottish artist J. D. Fergusson, essays on art and literature, poetry, and fiction, including six stories by Katherine Mansfield. Rhythm has been digitized by the Modernist Journals Project, and you can look at it here.